Major Paul Hildreth submitted his military registration card on February 14, 1942 while working as an accountant for DuPont in Sylacauga, Alabama. Facing a draft, he enlisted in the Air Force Reserve on May 22, 1942, at which time he was subject to a physical examination. He was activated as an Aviation Cadet applicant on October 23, 1942.

Aviation Cadet Qualification

As ordered, Paul reported to the Cadet Corps Classification Center at Kelly Field in Nashville, Tennessee on October 28, 1942 to determine if he would train as a navigator, bombardier, or pilot. The U.S. Army Air Forces imposed exacting standards for future pilots which was his preference. Just months before, in January, the Army Air Forces instituted qualifying exams based on rigorous psychological research instead of a blanket two-year college education requirement that would have prevented Paul from becoming a pilot. The new approach judged candidates by a three-part battery of tests, specifically the Aviation Cadet Qualifying Exam consisting of several parts (vocabulary, reading comprehension, practical judgment, mathematics, alertness to recent developments, and mechanical comprehension), multiple psychomotor tests (eye-hand coordination, reflexes, ability to perform under pressure, and visual acuity), and an interview with a trained psychologist. Cadets were subjected to three hours in a low-pressure chamber to simulate an altitude of 30,000 feet in order to determine an ability to withstand high altitude flying. Additionally, there was an extensive physical examination for flying. Paul appeared before the Aviation Cadet Examining Board while waiting days for tabulation and analysis of all tests. 38 percent of his class (43-H) was disqualified for pilot training. The Board qualified Paul as an aviation cadet and the Flight Surgeon in Nashville certified Paul as qualified for high altitude flight on November 12, 1942. On that date he was accepted for active duty. Soon, Major Paul Hildreth left his new wife at her parent’s home to start pilot training. Each stop on this journey required Paul to master flying more powerful airplanes while performing more complicated tasks.

Pre-Flight School

Paul received orders to start Pre-Flight School at Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama on December 28, 1942. As shown by his nametag, he was in Squadron 5 of class 43-H (with the ‘H’ – the eight letter – designating that, if successful, he would receive his pilot wings in August, as he did).

The stated objective of Pre-Flight School was: “The preparation of Aviation Cadets, both physically and mentally, for intensive flight training in the Air Corps.” The nine week course of instruction was tightly structured in two parts. The first half was a ‘boot camp’ on basic military comportment, military developments, close order drill, gunnery and marksmanship, and strenuous physical conditioning to handle the rigors of flying combat aircraft. Concentrated academics in the second half focused on the basics of aeronautics and physics, along with mathematics, codes, maps and aerial photos, and air, ground and naval identification. Cadets learned to recognize certain aircrafts from three different angles, as can be seen from M.P. Hildreth’s aircraft recognition log where he was praised for his “good descriptions.” Paul’s class 43-H had 4,123 students, but 11 percent were either held-over to take the class again or outright eliminated from further pilot training. Pre-Flight School ended on February 26 when Paul received his Cadet Wings and was promoted to Pilot School. Paul’s preference was noted as transport pilot. On his Army Air Force Training Command overall Proficiency Card, Paul was found “genial, sincere, diligent.”

Primary Pilot School

To the Army Air Corps, primary pilot training was designed for the cadet to “fly a light and stable aircraft of low horsepower.” Training started on February 28, 1943 at the 51st Army Air Force Flying Training Detachment at the Alabama Institute of Aeronautics located at Van de Graaff Field in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. His nametag showed that he was in Group VIII of Class 43-H.

Paul’s Pilot’s Log indicates that his first flight was on March 4, 1943. By the end of April, Paul had completed the required 60 hours of flying a PT17 Stearman bi-plane, including 28 hours of dual flying and 32 hours of solo flying. Overall, one in four cadets failed Primary Pilot School. As one trainee noted: “Pilots couldn’t wear their goggles on their forehead until they soloed and that was one proud day when you could wear your goggles on your forehead … like a true flyer.” Paul received a furlough for eight days due to the death of his only sibling. After completing Primary Pilot School on April 29, Paul’s preference was to serve as a fighter pilot but was recommended for Medium Bombardment.

Basic Pilot School

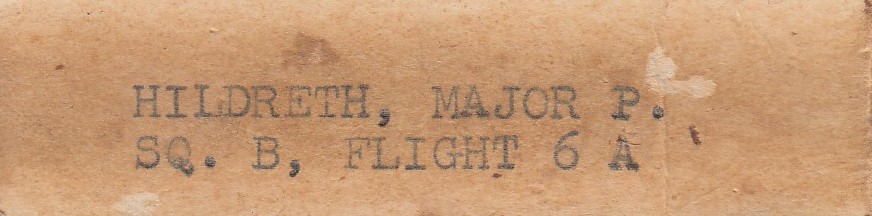

Paul was then ordered to Greenville, Mississippi to begin Basic Flying School on May 1, in Class 43-G, Squadron B, Flight 6A. There he learned to fly a BT-13a single-engine aircraft, a heavier plane than before and with more complex controls. From his first flight on May 3 until his last on June 26, Paul had logged 74:30 hours, with 41:30 hours of solo flying. Intensive training ranged from the classroom, link trainers, fly at night, and formation flying, to a solo cross-country flight. The Greenville Army Flying School was a demanding effort to prepare future pilots to achieve one goal, as the post commander stated: “victory” in the war. At the conclusion of training on June 30, Paul’s flying preference was as a fighter pilot, as was his recommended assignment. Paul’s Proficiency Card noted his “quick reactions” but that he was “liable to be careless.” Family lore suggests that his ‘careless’ behavior may have arisen due to his low-flying over his wife’s family house in Banks, Alabama and, on another training flight, flying under a river bridge. As a cadet, Paul was paid $75 monthly, plus flight pay. To make ends meet since Annie accompanied him, she found work in Greenville which was apparently her first job as she applied for and received her Social Security card in Mississippi.

Advanced Pilot School

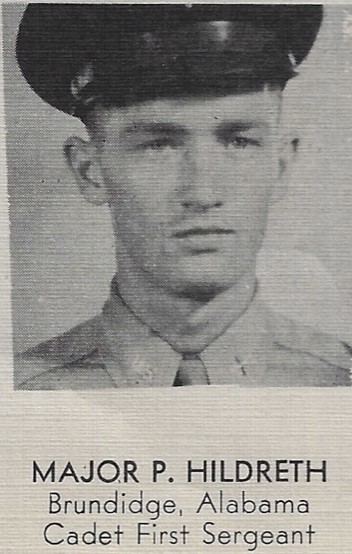

Paul Hildreth was then ordered to Stuttgart, Arkansas for Advanced Pilot training to start on July 2, 1943. He was a member of class 43-H, assigned to Squadron V, and selected as Cadet First Sergeant. It was at Stuttgart Army Air Field that Major received his most intensive level of flight training. He was assigned to multi-engine aircraft with characteristics similar to combat aircraft. From his first flight on July 6 until his last flight on August 24, Paul logged 31:06 hours of dual flying and 41 hours of solo flying in the Beechcraft AT-10 ‘Wichita’ [Interestingly, his younger son later lived less than one mile from the Beech facility in Wichita].

Paul completed several tests during advanced pilot training to access his competency in multiple areas of pilot training including (but not limited to): plane formation, navigation, plane engineering, first aid, radio, duties of an aircraft commander, and bomb approach theory. Here, his Proficiency Card described him as “calm and collected.” Physical fitness records reveal Paul, at 5′ 8″ and 130 pounds, achieved a ‘good’ rating which was in the middle category of scores compiled from sit-ups, pull-ups, and shuttle-runs. He was subject to another extensive physical examination for flying.

As stated in the local newspaper, Paul was “awarded the wings of a flying officer and a commission as a Second Lieutenant in the Army Air Force” in “the second class to complete the intensive training course at this two-engine advanced flying school.” Upon graduation of Advanced Pilot School, Paul’s flying preference had changed to Medium Bombardment as was his recommended assignment. A pilot transition training record concluded that “This student is average in most phases of his flying. Needs more altitude formation. Steady. Dependable. Not recommended for instructor.” However, in his official proficiency report, Stuttgart recommended him as an instructor.

Aviation Cadet status ended on August 29. On August 30, Paul received his Pilot wings, took his oath, and entered Active Duty as a “temporary Second Lieutenant” (a five year commitment) and graduated from the Stuttgart advanced pilot training program. During primary, basic and advanced pilot training, Paul totaled 206:36 hours of flying, with 114:30 hours of solo flights.

B-17 First Pilot Transition School

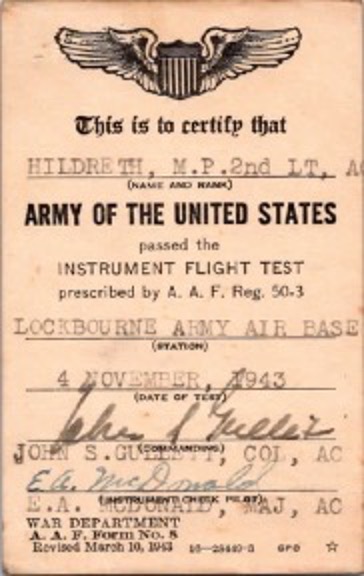

Paul was then assigned to a heavy bombardment (B-17) First Pilot transition training group on four engine planes (occupational code 1024) for two months at Lockbourne Air Base in Columbus, Ohio. He was there from September 11 to November 12, in Class 43-4-H. The schedule called for seven pilot trainees to each of the 60 airplanes at Lockbourne. Paul piloted the Boeing-built B-17E for the first month and then the B-17F during this second month of training. Flying included day and night instrument navigation flights as well as formation flying and a 10-hour mission to Fort Worth and return. He piloted 107 hours in the B-17. To be the pilot in command, he had to show proficiency in the duties of each of the other B-17 crew members. Training included passing the Instrument Flight Test and knowing the cockpit so well that it could be operated blindfolded by a test with a required score of 100 percent. As one author pointed out, there were over 150 switches, cranks, dials, and gauges in the B-17 cockpit to learn. The goal was to train pilots to act instinctively and without hesitation. Paul’s work culminated in achieving certification as a first pilot for B-17E and B17F planes on October 26 and for instrument flight on November 4. Paul’s Proficiency Card noted that he was “not easily excited. Applies himself well.” Annie accompanied Paul to Columbus in their 1941 Chevrolet Coupe.

B-17 Plane Commander Training

On November 13, he was officially transferred to the 18th Replacement Wing at Camp Kearns near Salt Lake City, Utah, where he was assigned a crew and a new location to start B-17 crew phase training.

The initial members of the crew arrived by train in Rapid City, South Dakota on December 5. They were assigned to the 398th Bombardment Group which was a replacement training unit before being assigned to a combat Bombardment Group. They were Crew #4 in the 601st Squadron of the 398th.

Paul started his role of as Plane Commander of the new B-17 crew at the Rapid City Army Air Base (now Ellsworth Air Force Base) on December 9 in a B-17F, although some crew members were assigned as late as Dec. 18.

As First Pilot and Plane Commander (occupational code 1091), Paul was responsible for the condition of the B-17 and the people assigned to his crew. He was to perform detailed inspection of the plane and maintain flight records and report observations made during a mission. Both the pilot and co-pilot had to follow a check list of B-17F duties before flight. The First Pilot had to have a thorough knowledge of regulations, meteorology and combat tactics, and pass the Instrument Flight Test.

Air crew training focused on three phases, with the first one the primary focus at Rapid City. The First Phase was devoted primarily to individual training in instrument flying, navigation, night flying, bombing, and aerial gunnery. Each crew member had their own particular skill training based on their assigned roles (e.g., gunner, navigator, bombardier). Additionally, “each combat crew member was required to have experience in high-altitude operation; knowledge of the tactics of air attack and evasion and of the principles of bombing; the ability to operate any gun position on the airplane; proficiency in radio-telephone procedures; the ability to identify friendly and hostile aircraft, armored vehicles and naval vessels; and the ability to engage in effective air reconnaissance.”

The second phase, on building crew teamwork, had an early start here. The crew worked on their coordination during target practice and simulated bombing runs. By flying in challenging weather conditions while enjoying the setting (such as flying around Mount Rushmore which was under construction), the crew developed a reliance upon one another as a combat-ready air corps team. Paul accounted for 38 hours as first pilot. They had their first crew picture taken (i.e., the one with winter clothes). Annie Lester got to know the crew members during her time with Paul in Rapid City.

B-17 Overseas Combat Unit Transition

On January 1, 1944, the Hildreth crew was one of 50 new combat crews transferred by train to the 483rd Bombardment Group (Heavy) at the Overseas Transition Unit School of the U.S. Army Air Forces based at MacDill Field (Tampa), Florida. Hildreth’s crew was one of eleven new crews assigned to the 816th Squadron on January 6th. The Group had received Warning Orders days earlier alerting it for oversees shipment on or about March 1st.

In preparation for high-altitude B-17 training and eventual deployment oversees, Paul signed for the appropriate equipment, including custom-fitted oxygen masks, a steel helmet with liner, other assorted items, as well as the flyers’ clothing kit that contained flying sun glasses and the all important electric suit, electric socks, and electric gloves. He received a canvas bag to hold the flying equipment.

The combat crews began formal Second Phase training on January 10th. Special focus was on the development of combat teamwork, with extensive training in bombing and gunnery operations, instrument flying, and formation flying.

As First Pilot and Plane Commander of Crew 617, Hildreth had to pass the Instrument Flight Test again and demonstrate complete understanding of a B-17F aircraft before receiving the certificate of proficiency and combat crew qualification for Pilot. In addition, each member of the crew accomplished hours of ground school on topics such as armament, bombing theory, communications, target identification, ditching, survival training, meteorology, medical, and security. Over the two months in Tampa, he was the B-17 first pilot for 162 hours and another 215 hours helping the co-pilot gain proficiency.

Third Phase training focused on the development of high-altitude formation flying, long-range navigation, target identification, and simulated combat missions in cross-country runs. As the Group’s history recorded, one flight was a 1500-mile over water mission to Whole Rock Island, off the Yucatan Peninsula, and another was to ‘bomb’ Charleston, South Carolina.

Paul was certified in formation flying on January 29. Overall, he had over 430 hours of flying time in aircraft, over 85 hours in flying over 20,000 feet, and 36 hours of formation flying over 20,000 feet, all critical for combat flying proficiency.

The famous ‘Memphis Belle‘ (42-24485) B-17 was assigned to the 483rd on January 1, 1944, and Hildreth piloted it during crew training at MacDill Field. Crew gunner Mel Wylie wrote in 1979 that the Memphis Belle is “probably the only B-17 still in existence that we did fly in.” Later, in 1981, when crew member Wylie was able to touch the Memphis Belle during her restoration in Memphis, his wife wrote Paul that “I have never seen Mel so chocked up, when he saw her –clearing his throat, wiping his nose, and tears in his eyes….Mel was seldom emotional so the thoughts surrounding this old plane and the years with the crew meant a lot to him.”

A new B-17G, number 42-107008, was delivered to the Army Air Force on January 24, 1944 and transferred to MacDill on February 14. Paul and his crew were the first to fly ‘008 on a training mission after its delivery to MacDill. Paul piloted this B-17 over the Atlantic and during combat missions including the last one.

While at MacDill, as the navigator recalled, Paul and his crew watched one of the new B-17s “catch fire on a parking stand and (saw) that it only took minutes to become a heap of ashes. Hildreth got the whole crew together and we agreed that in case our plane was ever to catch fire, nobody should wait for a bail out order but to jump as soon as possible.” This proved to be a prescient procedure for handled their last combat mission.

Crew members confronted their upcoming combat reality by having to complete forms such as a superseding last will and testament and details on family contact information and how their bodies should be handled “in case of decease.” They were instructed in what to do overseas in combat operations. Paul was subject to another extensive physical examination for flying.

On March 1, they flew ‘008 to Hunter Field in Savannah, Georgia for the 816th Squadron’s processing for overseas duty. Here they received new equipment and clothing.

On March 8, Paul piloted ‘008 to the Embarkation Station at Morrison Field (now Palm Beach International Airport), Florida where they received sealed orders, likely with other details on their secret flight path that they were not to open until one hour into the rainy day flight. They were authorized a flat amount of $7.00 per day for their travel to the final destination. On March 10, they started the secret flight itinerary as part of the 816th Bomb Squadron, 483rd Bombardment Group. First came a 10 hour flight, with a short fuel stop in Puerto Rico (likely Borinquen Field in Aguadilla), to Waller Field in Trinidad.