As crew commander, M. Paul Hildreth led his crew on their secret overseas itinerary starting March 12, 1944, when they departed Trinidad’s Waller Army Airfield in B-17G #42-107008, for the 7 hour flight to Belem Airfield, Brazil. The next day, after a short maintenance fix, they had a 6 hour flight to Parnamirim Field in Natal, Brazil, which is the closest point to Africa.

In Natal, the planes were thoroughly inspected, and extra fuel tanks installed in the bomb bays for the flight across the Atlantic. They took off the next day but engine problems three hours out over the Atlantic required a return for repairs. However, the problem was not resolved, as the following day’s flight also required a return for repairs, this time just after take-off. It took about a week for the engine to be fixed after parts were flown in for the repair. While the rest of the 483rd group was well on its way to Italy, Paul’s flight was delayed until March 22 for the 2,000 mile, 11-hour flight to Dakar, Africa. The navigator used celestial navigation on the flight. Once they arrived in Dakar, they became part of the North African Theater of Operations (NATOUSA), and began their flight itinerary up the African continent to Italy.

The Hildreth crew was delayed upon leaving Dakar, this time due to a long-lasting severe dust storm. Finally, Paul piloted the 7-hour flight up the coast to Marrakech, Morocco on March 25. After another delay due to mechanical issues, finally, on March 31, the crew flew the 7 and a-half hour flight to Djedeida Airfield near Tunis, Tunisia. The last leg of the trip was a 4 and a-half hour flight on April 3 to Tortorella, Italy.

Their arrival in Tortorella Airfield on April 3 marked the beginning of their preparation for combat missions. They were Crew 617 of the 816th Squadron of the 483rd Bombardment Group (Heavy), 5th Bomb Wing of the 15th Air Force. After conducting days of training missions, the Group executed its first bombing mission on April 12 from Foggia, Italy. On April 22, the Group relocated to a newly built tent camp and steel mat runway at Sterparone Air Field, located in Apulia, Italy, approximately 6 miles southeast of Torre Maggiorea. To accommodate both the military and social needs for 1,800 men, the camp expanded with many activities (as chronicled in the camp’s paper ‘The Latest Poop‘) and new buildings.

The importance of the air bases on the “plains of Foggia” were described by ‘Hap’ Arnold, Commanding General of the Army Air Forces, “as one of the keys to the liberation of Europe, for it was there that the Allies drove in order to base the strategic heavy bombers which were to fly in Adolph Hitler’s ‘back door’ and help destroy his war machine.” Southern Italy was viewed as “a base for an air force that could strike at the Balkans and at the industrial plants moved by the Germans beyond range of British-based bombers.” This area “became a staging area for flights to targets in southern Germany and Austria.” Bombing missions focused on the ball-bearing industry, oil refineries, airfields and related “Nazi war machine” targets.

Donald L. Miller, in his book Masters of the Air: America’s Bomber Boys Who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany, aptly framed a pilot’s combat life: “Chance was the all-determining force in an airman’s life. It determined the composition and character of his crew, his plane’s position in the combat formation, the weather his formation flew into, the intensity of enemy opposition, and ultimately whether he lived or died.”

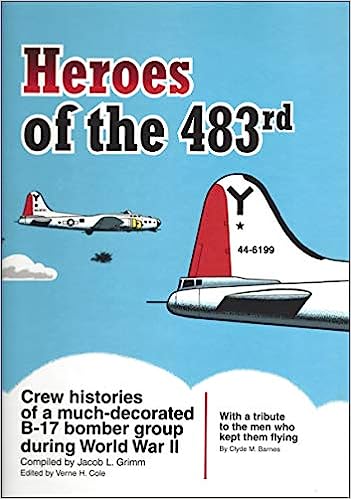

As a key component of the “liberation of Europe,” B-17s of the 483rd Bomb Group had distinctive red tail rudders along with Y-star markings. Additionally, each squadron had distinctive engine cowling colors, with the 816th Squadron’s painted yellow, to allow pilots to easily form into their appropriate squadron. 816th planes are shown in this 1945 picture and as illustrated on the book cover of the ‘Heroes of the 483rd’ published by the the 483rd Bombardment Group (Heavy) Association.

Hildreth piloted 37 strategic bombing missions of Crew 617 for the 816th Squadron in a ‘Flying Fortress’, as B-17s were called. A large support team was required for each B-17. The 816th Squadron had 18 flight crews.

Paul’s commanding officer took the relatively new ‘008 aircraft on as many missions as he was allowed to fly. While most of the Hildreth missions were conducted on B-17G #42-107008, he also piloted combat sorties on #2102836 (nicknamed ‘Lyla Lue’), #124421 and maybe others. Interestingly, the Hildreth crew referred to ‘008 as “The Old Bird” to reflect its durability over so many combat missions. The nickname of ‘008 is listed as ‘Flak Off Limits‘ in some accounts, although not by Paul.

As was procedure, crew members recorded their missions. The number of missions for rotation out of the war zone changed with command leadership, with 50 missions soon set by the Group. The log of missions by Hildreth’s Crew #617, termed the “The Best Crew in the Whole Damn Outfit,” records each mission by noting what was bombarded, length of mission if relevant, fighters seen, flak holes, and damage done. These strategic bombing missions focused on marshalling (railway) yards and oil refineries. The typed log includes personal notes, for example, comments on the mission in Venisoieux, France on May 25, 1944: “Longest mission ever pulled from here. 7.5 hours. Marshalling yards and round houses. Smashed target. Flak, heavy type. 15 fights, but we weren’t able to see them. Up to now, I haven’t fired a round of amo [sic].”

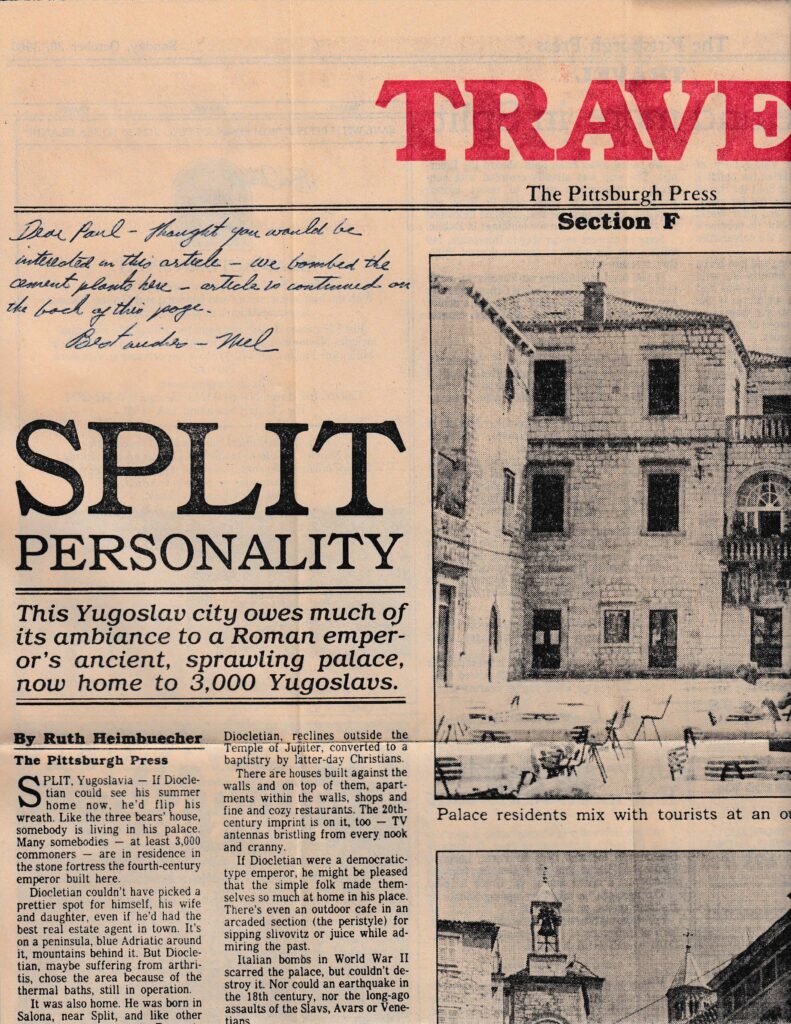

The crew’s first bombing mission, on April 12, 1944, was to Split, Yugoslavia, where their Group “plastered” a cement factory. There was heavy flak that shot out #2 engine and led to three holes in the plane. As a result, the Hildreth plane had to leave the formation without bombing the target and head home with what the co-pilot termed a “free wheeling non-feathered propeller … [in] our initiation of fire.” Even though they did not drop their bombs on that target, the crew got combat mission credit since they faced flak and guns. In 1983, crew member Mel Wylie sent Paul a newspaper clipping about Split, Croatia with this note: “Dear Paul- thought you would be interested in this article- we bombed cement plants here- article is continued on the back of this page. Best wishes- Mel.”

One day after D-Day, Major Hildreth and several other officers were ordered to the Naples Metropolitan Area for an unspecified official business matter concerning the Squadron Commander, but there is no entry in his pilot log. More than likely, this trip was for rest and relaxation at the Rest Camp on the Isle of Capri. The officers made their way to Rome just days after the advancing American army arrived. While they were gone, eight flight crews from the 816th Squadron participated in the 5th Bomb Wing’s first shuttle bombing mission to Russia to stage bombing missions from there.

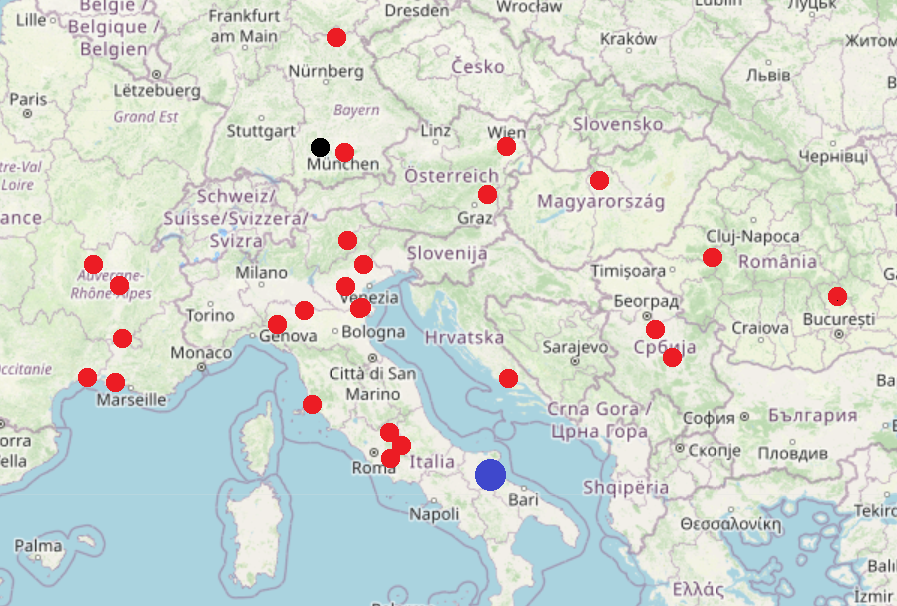

On July 7, Major Hildreth’s crew bombed the North oil refinery at Blechhammer, Germany, close to Auschwitz. They faced “terrific flak” but they “smashed target.”

The range of a fully loaded B17G ‘Flying Fortress’ to a bombing target was just over 1,000 miles. The targets of the missions conducted by first pilot Paul Hildreth and his crew are conveyed in this map with red dots to show the approximate location of the bombing targets, with the blue dot representing Sterparone Air Field where flights originated and the black dot representing Memmingen, the crew’s last mission. Several of the targets were hit several times, on different days. All flights were part of daylight bombing missions carried out by a massed formation of bombers, with expected protection provided by a contingent of fighter aircraft.

According to ‘Hap’ Arnold, Commanding General of the Army Air Forces, the number one oil target in Europe was Ploesti, Romania. The Hildreth crew hit it three time. First, on June 23, where they faced lots of heavy, but inaccurate, flak. They hit a refinery despite bomb trouble. The last entry in the crew log (mission #35) is a bombing run to Ploesti, Romania on July 9 where they targeted an oil refinery while taking “lots of flak and fighters.” Paul’s individual flight records reflect that the next mission (not logged in to the crew list as #36) was to the same location on July 15, apparently to complete the destruction of a vital war facility. In fact, co-pilot Worcester confirmed this mission and is quoted (by his granddaughter Heidi M. Klise in 2012) as saying “we really plastered them.”

Paul’s combat flying service earned a monthly pay as “… a second lieutenant drawing base, flying, oversees, and subsistence in the amount of $349.50. I have a Class E Allotment of $200.00 and [life] insurance of $6.50, total deductions of $206.50, leaving net pay received of $143.00.” The Class E Allotment was the amount paid directly to his wife. (The monthly amount of $349.50 is equal to the inflation adjusted amount of $6,090 in early 2024).

As of July 16, 1944, Paul’s individual flight records reflect a career total number of flight hours of 764 hours and 10 minutes and first pilot time of 412 hours and 15 minutes. But that was before combat mission #37 that was attributed to Paul by his Squadron Commander: a flight of 6 hours and 40 minute as first pilot on July 18, 1944, targeting the Memmingen Airdrome in Germany.