As crew commander at age 23, Paul Hildreth led his B-17 crew with an average age of 22 on over 400 hours of flight time together as a team, working in close quarters in a unforgiving environment.

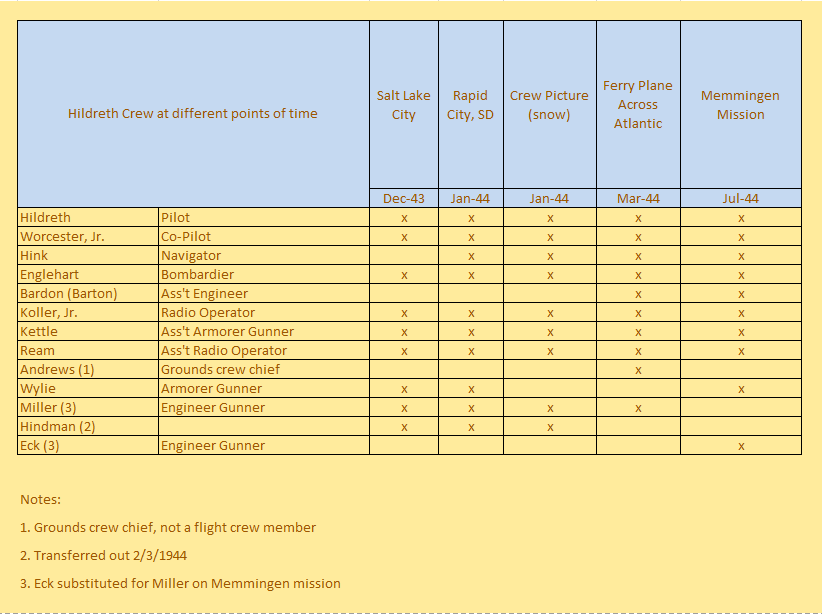

The crew included four commissioned officers, all Second Lieutenants: pilot Major Paul Hildreth; co-pilot Winthrop S. Worcester Jr.; navigator Frank Lewitt Hink; and, bombardier William H. Englehart. Worchester and Englehart met Hildreth in Salt Lake City, and Hink joined the crew in mid-December in Rapid City, SD. The remaining six crew members were enlisted men who were assigned to the Hildreth crew in Rapid City. Over time there was some changes in the enlisted crew membership, as shown in this table.

As shown, most of the crew remained the same from Rapid City, South Dakota to the last mission. This team bonded as they handled the rigors of training and the time together in the unforgiving cold of high altitude flying and the dangerous flights over enemy territory. All the crew members on the Memmingen mission parachuted out of the airplane before it spiraled out of control and crashed. After surviving the jump, all were captured and endured the P.O.W. experience. More importantly, they all returned to America to enjoy the rest of their lives and family.

Reunion

Many of the crew members kept in touch over the years, as confirmed by infrequent letters sent to Paul and also by several of them visiting Paul and Annie in Banks, Alabama. Finally, in September 1983, six members of the crew joined Paul in their first reunion that was held during the 483rd Bombardment Group Association annual meeting in Dayton, Ohio. A year earlier, Paul and Annie Lester hosted co-pilot Winthrop Worcester and wife Jane in a dinner at a business club in Win’s home town of Akron, Ohio. [In both settings, Paul’s youngest son and wife, given their home in Kent, Ohio, enjoyed the opportunity to experience the crew’s tight bonds and hearty remembrances.] In a newspaper interview in October 1983, Paul commented: “At this last reunion they had to remind me of a few stories I had forgotten. But I’ll never forget what happened July 18, 1944. Distance may separate my crew, but we’ll always be close.”

Crew Profiles

Here is a profile of each member of the Hildreth crew based on the limited information found in Paul’s files or online. We welcome family members submitting information to provide more detail on their veteran.

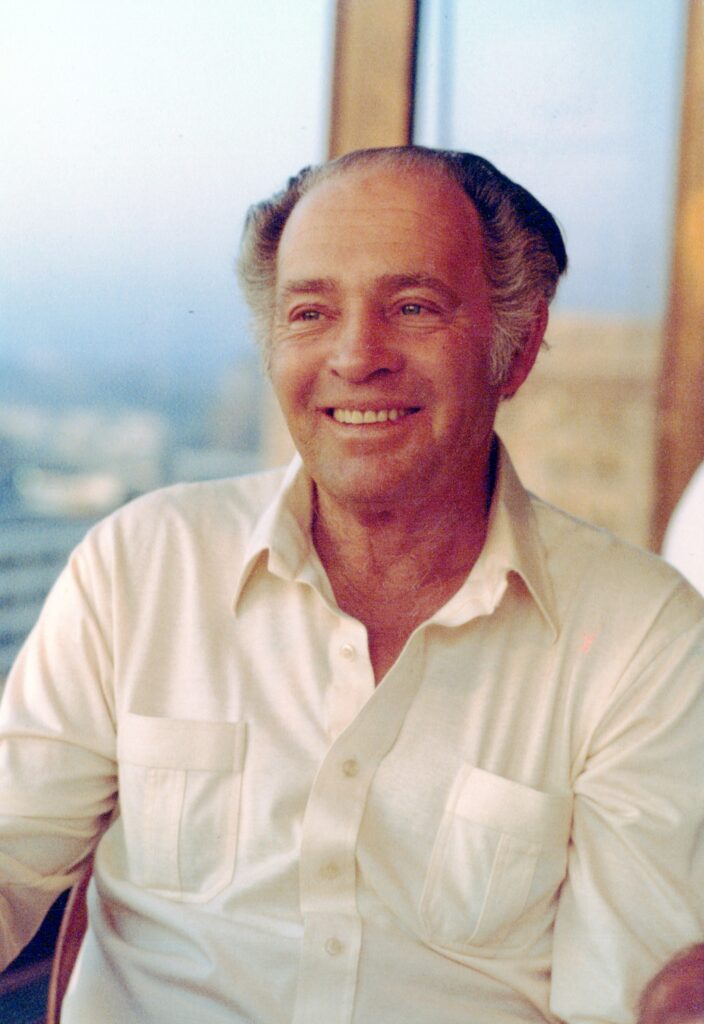

Co-Pilot Winthrop Sargent Worcester, Jr. was originally from Elwood City, PA but later built a career and life in Akron, Ohio. In Rapid City, ‘Win’ Worchester received first phase training and later in Tampa he completed the 483rd Bombardment Group’s instruction for Pilot and was qualified to perform the duties of Co-Pilot in an aerial combat crew. Crew member Wylie pointed out to Hildreth, in a 1979 letter, of Worchester “practicing aerial maneuvers (such as trying to fly) when he bailed out, before he pulled the rip-cord.” Worchester reported that after parachuting he was captured in Kempten on July 19 at 0600. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered his military ‘dog tag’ and the formal record (English translation) of his capture. Worchester and Hildreth were housed in the same P.O.W. compound. An oral history of his experiences during the war and his P.O.W. life is beautifully profiled by his granddaughter in her university honors thesis (Klise, 2012). Paul and ‘Win’ (with their wives) enjoyed their first time together since the War at a dinner in Akron in 1982. Winthrop was born on January 27, 1921 and died on January 15, 2015.

Navigator Frank Lewitt Hink was born September 9, 1916 in Eureka, California. He graduated from the University of California-Berkeley and was from San Leandro. In Rapid City, Hink received first phase training and later in Tampa he received a certificate of proficiency and combat crew qualification for Navigator. Reflections from co-pilot Worchester (Klise, 2012) highlight the pre-combat comfort the crew gained of Hinks’ navigational skills when he nailed the coordinates to ‘target’ a sunken ship in the Yucatan peninsula in a training flight from Tampa, pinpointed the headings across the Atlantic Ocean to get them directly to Dakar on the African coast, and instructed the pilot on when to make sharp turns through the Atlas Mountains in North Africa. Although, as Wylie reminded Hildreth in a 1979 letter, Hink almost bombed the drive-in in South Dakota instead of the night bombing range. Hink was injured before bailing out of ‘008 in the Memmingen mission. He later reported that he was captured near Ravensburg on July 18 in the afternoon. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered his military ‘dog tag’ and the formal record (English translation) of his capture. In the P.O.W. camp, Hink and Hildreth were housed in the same room in P.O.W. camp. After working for Merrill Lynch in NYC, he returned home to work in the family clothing store. Hink died on September 3, 1996 in San Leandro, California.

Bombardier William Harold Englehart was from Oak Park, IL. In Rapid City, he received first phase training and, later in Tampa he received a certificate of proficiency and combat crew qualification for Bombardier. After parachuting, he later reported that he was captured in the neighborhood of Ravensburg on July 19 at 12:00. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered his military ‘dog tag’ and the formal record (English translation) of his capture. He and Hildreth were in the same P.O.W. camp and saw each other several times a day. In Englehart’s 2003 obituary, his brother is quoted as remembering Willie’s return from the war: “When he got home, he gave us the whole story and when he was finished, which was sometime in the morning, he said he never wanted to talk about it again. He was lucky to get out of there because they really didn’t feed them. He weighted about 125 pounds when he came home.” He was born on October 28, 1923 and died on January 17, 2003 in Stuart, Florida.

Radio Operator Charles John Koller, Jr. was from St. Bernard, OH. He was born on January 11, 1923 and enlisted on January 23, 1943. In Rapid City, Koller received first phase training as Radio Operator and Mechanic Gunner (757) and then in Tampa he received the certificate of proficiency and combat crew qualification for Radio Operator. He was injured before bailing out of ‘008 in the Memmingen mission. He landed in a tree with a badly wounded leg. He was captured on July 18 and taken to a hospital in Ravensburg. In the evening of July 24, he was turned over to military control. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered his military ‘dog tag’, the formal record (English translation) of his capture and a list of confiscated items (English translation). Koller died on February 27, 2018 in St. Bernard, OH.

Assistant Armorer Gunner Paul Seward Kettle was from Atascadero, CA. He was born on February 9, 1924 and enlisted on February 2, 1943. Originally, Kettle was a Flight Maintenance Gunner (748). Kettle received first phase training in Rapid City and in Tampa he received a certificate of proficiency for Radio Operator but was deemed qualified to perform the duties of Assistant Radio Operator in an aerial combat crew by the 438th Bombardment Group. As an armorer, Kettle was responsible for loading bombs and on the ship his position was as tail gunner. As the tail gunner, he was injured before bailing out of ‘008 in the Memmingen mission. According to an official account by navigator Hink: “Kettle didn’t see the fire and backed out of the tail just in time to grab his chute when he saw the rest of us jumping. He fell out of the plane when the tail broke off, attached his chute, then had to pull it open by hand when the rip-cord didn’t work. The chute opened at minimum altitude – he had some small flak wounds.” Kettle later reported that he was captured near Ravensburg on July 19, shortly after 12:00. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered the formal record (English translation) of his capture but not his military ‘dog tag’. In a letter to Hildreth in 1983 right after their first reunion, Kettle wrote: “Being around you for a few days made me feel like I was rubbing shoulders with royalty. I shall never forget it as long as I live. We sure had a great crew.” Paul Kettle died on July 18, 1993 — 49 years to the day of the Memmingen mission!

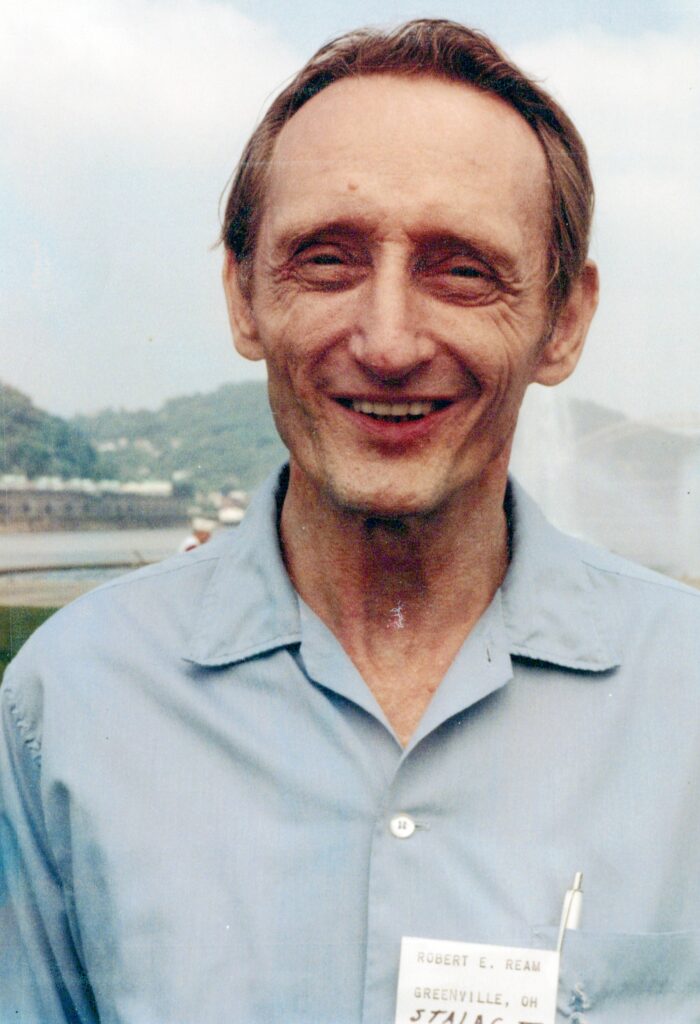

Assistant Radio Operator Robert Emerson Ream was originally from Greenville, OH. He was born on April 24, 1924 and enlisted on March 4, 1943. Ream received first phase training in Rapid City and in Tampa the 483rd Bombardment Group qualified Ream as an Armorer Gunner (612) in an aerial combat crew. In the Memmingen Mission, Ream, as ball-turret gunner, experienced a direct hit but able to abandon the plane with help from others, although they could only get one side of his chest parachute to hook. When he hit the ground (near Hildreth), he was still in daze and the chute snapped him hard. He suffered a severe head injury upon landing among rocks. Ream was further subjected to mistreatment by German civilians who threw bricks at him. He was captured near Kempten on the morning of July 19. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered his military ‘dog tag’ and the formal record (English translation) of his capture. Ream was a P.O.W. at Stalag-Luft IV in Gross Tychow, Pomerania, with physical injuries that made him unable to get out of bed most of the time. That camp was evacuated and in the process of being transferred, Ream was subjected to a difficult train ride due to his injuries. Eventually, he was transferred to the same P.O.W. camp as Hildreth, in Barth. Years later, Bob Ream had difficulty in getting adequate military recognition for his war time injuries. He visited Paul and Annie in Banks, Alabama. He died on June 3, 2002 and is buried in Arcanum, Ohio.

Assistant Engineer Robert Bruce Bardon was born on September 28, 1918 in San Francisco, CA. He enlisted on August 7, 1942. He was listed as a Flight Maintenance Gunner (748). The 483rd Bombardment Group said he was fully qualified to perform the duties of Assistant Engineer in an aerial combat crew. Bardon was injured before bailing out of ‘008 in the Memmingen mission. According to the Navigator’s account, “Bardon claimed he was blown out of the upper turret and was entangled in his chute so that he landed on his head.” Bardon later reported that he was captured near Ravensburg around noon on July 18. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered his military ‘dog tag’ and the formal record (English translation) of his capture. Bardon’s combat injuries led to later disability claims. Before heading overseas, he wrote a poem entitled “Combat Mission” that was given to Paul and Annie. (We gave the typed original to the Bardon family in 2023 since they were not aware of its existence). He died on July 3, 1977 in Omaha, Nebraska.

Waist Gunner and camera man Melville Wrenshall Wylie was born on June 25, 1922 and at the time of his military service, he was from Wilkensburg, PA. He enlisted on October 2, 1942. In Rapid City, Wylie received first phase training for a combat crew as an Aerial Gunner (611). An original Hildreth crew member, he briefly joined the Gleason crew for the flight overseas. Later, he was listed as an armorer, so Kettle was responsible for loading bombs. On the plane, he was the waist gunner. After parachuting, Wylie was captured in Kempten on July 19, in the afternoon. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered his military ‘dog tag’ and the formal record (English translation) of his capture. He died on June 22, 1984 and is buried in Wilkinsburg, PA.

Engineer Charles Herman Eck was born August 23, 1924 and was from Muskogee, Oklahoma. As the engineer on a combat crew, he was a member of the Dale Swails crew, and participated in the shuttle missions to Soviet airfields that facilitated bombing missions to certain parts of Germany. According to crew member Ream, Eck volunteered to take the place of Lewis Miller of the Hildreth crew on the Memmingen mission. Eck later reported that he was captured on July 18 in the afternoon near Ravensburg. After the war, by seizing German documents on downed aircraft, the U.S. government recovered his military ‘dog tag’ and the formal record (English translation) of his capture. Eck later became a commissioned officer and then worked with General Electric Corporation. He retired to Melbourne, Florida. Eck died on August 19, 2021 and is buried in Muskogee.

Lewis H. Miller was born on September 17, 1917 in Bonifay, Florida. He enlisted on March 9, 1942. Miller received first phase training in Rapid City as an Airplane and Engine Mechanic (747) and in Tampa he was qualified as Engineer in an aerial combat crew. Lost to history is the reason why Miller missed flying on the Memmingen mission with the Hildreth crew, with Eck substituting for him. Subsequently, Miller became a member of pilot Colin J. Walker’s flight crew.

Roy G. Hindman was born on October 7, 1923 in Mt. Harris (Routt County), Colorado. He enlisted on December 12, 1942. In Rapid City, Hindman received first phase training as a Airplane and Engine Mechanic (747). He was reassigned from the 483rd in MacDill due to too many mechanic-gunners (748) on the Hildreth crew. He flew with the 668th during WWII. He went on to have a distinguished career in the U.S. Air Force with service in Viet Nam, and retiring as a Major. Hindman died on January 22, 2012 in Chubbuck, Idaho and is buried in the Fort Logan National Cemetery in Denver.

Steven Andrews, the ground crew chief, was born in Pennsylvania in 1922 but enlisted on November 4, 1942 in New York, NY. The two ground mechanics who assisted Andrews are not identified in the records.