On July 18, 1944, after a 0430 briefing and a take-off at 0650, Paul Hildreth, and his crew, embarked on his 37th combat mission in the four-engine B-17G they referred to simply as ‘The Old Bird’. It was a perilous 500-mile mission to attack the Memmingen Airdrome in Germany, near Friedricshafen, as part of the 483rd Bomb Group, 816th Squadron. This mission was considered so important that 167 B-17 type airplanes of the 15th Air Wing were dispatched. The Memmingen Raid, as it became known, was later documented in the Tampa Times and in several reports and articles cited in the Resources section including some from Germany with English translations provided.

Recall Notice Not Received?

The 483rd Bomb Group was in the fifth of the six-wing formation on that fateful day. While poor weather conditions over the northern Adriatic made most of the planes return to base or attack alternative targets and enemy radio stations sent out confusing information, the 483rd continued on to the primary target due to the “absence of a properly authenticated recall signal.”

Despite that official statement, the 816th Squadron Commander Fred J. Ascani (later a Major General) wrote in 1985 that the 483rd Deputy Group Commander, Lt. Col. Willard S. (Will) Sperry, “had heard the recall message but decided to ignore it. He also added that he pretended to have a communication failure hence he never heard the message. You can understand my bitterness when none of my crews returned from that mission. Since the 7 aircraft from my squadron where at the end of the trail formation, the enemy fighters chewed them up like so much butter….”

Exposed and Shot Down

On a beautiful clear day, flying at a bombing altitude of 23,500 feet and about three minutes before the 483rd approached its assigned Initial Point at 1045, the expected 90 degree turn into its bombing run was disrupted as the B-17 Group found itself without fighter escort and facing 75 enemy fighters (Messerschmitt 109s and Focke Wulf 190s), joined later by another 75 fighters. The expected fighter escorts of P-51 Mustangs from the 332nd Fighter Group, known as the Tuskegee Airmen, did not arrive as expected. Thus, the B-17s were left exposed to attacking German fighters. After about 10 minutes of slaughter, a group of 36 P-51 fighters from the 31st Fighter Group came to help the surviving B-17s.

The 483rd was comprised of four boxes of seven B-17s each. The fourth box, in the rear, contained the seven B-17s of the 816th Bombardment Squadron. Under standard procedure, the 816th held that last box position in the formation because it had been the lead squadron the day before. In addition to the 10-men, each plane had 100-octane fuel, ammunition, and twelve 500-pound bombs.

The Hildreth plane was listed in the 483rd Group’s official records as being in the front left of box four (position 3) but later research suggests it may have been in the front right (position 2). Given the attacks on his plane, Paul reported that he had to leave the formation about 30 miles Southwest of the target. He was piloting B-17G #42-107008 which was the same airplane that his crew had been assigned in Tampa and ferried across the Atlantic. They referred to ‘008 as simply ‘The Old Bird’ due to their many flights in this reliable and stable plane. Even on that fateful day, ‘The Old Bird’ lived up to its name as long as it could.

In this epic air battle, the enemy fighters focused their first attack on the seven planes in the fourth box. All of these B-17s were destroyed either initially or after severe attacks despite the B-17 crew gunners shooting down many of the enemy fighters. After destroying the seven planes of the 816th, the enemy fighters focused on seven more B-17s on the outer edges of the right and left boxes. Despite the fierce air battle against overwhelming odds, the remaining B-17 crews were able to continue to the target and accomplish devastating damage to the Memmingen Airdrome. The Hildreth gunner crew shot down five attacking fighters before ‘008 was itself too damaged to continue. A later speculation was that “An enemy Focke Wulf 190, possibly flown by Gefr. Erich Erck of II./JG3 came in at five o’clock attacking Lt. Hildreth’s plane catching it on fire….” Fighter pilot Erck was killed during the air battle.

The Hildreth plane developed fires and complete loss of control from 20MM shell direct hits. Paul later typed this account: “My ship was severely damaged by enemy fighters. The electrical system was shot out. Later, we lost three and four engines, then the no. 2 main tank burst into flames. At this time I had the Co-Pilot notify the crew to bail out. Three of the crew members were slightly injured, all were taken prisoners …. My crew accounted for five enemy fighters. I stayed with the ship until she started to spin, then I bailed out and saw the ship blow to pieces.”

In a handwritten account, Paul offered more details: “We were aware that we would soon have to leave our ship however we could see no immediate danger until the flight deck was filled with smoke. I looked around and saw the left wing ablaze. I immediately called the co-pilot to bailout. He notified the crew and after a short time (but seemed an eternity), I saw that I would have to leave the ship. She had just started into a spin. I removed my equipment and crawled to the escape hatch and took that final jump. I opened my chute immediately and watched my ship start to spin then disintegrate. I was startled at the sky that was filled with pieces of ships and so many chutes; it was like a dreadful nightmare.”

Paul’s interview and story in his local newspaper in 1983 revealed this aspect of his struggle to exit the airplane: “When we were hit by German fire, four fires started in our plane. Everyone had bailed out, but me. The gravitational pull was so great, I couldn’t get out. So I started playing around with the automatic pilot switch in order to stabilize the plane. It worked, and I got out.”

That’s when I told [Paul]…to get out first and he told me where to get off

Pilot Hildreth’s cursing response to Co-Pilot Worchester who asked to be last out of the plane, as recounted by Worchester to his granddaughter Heidi Klise (2012)

Crew members provided details on the last minutes of ‘008 for the archives of the 483rd Bombardment Group (H) Association. These accounts were published in the Association’s 1997 book, Heroes of the 483rd (pages 101-102):

Co-pilot Worcester‘s statement: “The first wave of enemy aircraft from my vantage point was a solid line from one o’clock to five o’ clock. I watched the FW-190 that got us as he approached along the right wing with his guns blazing. Large gaping holes popped up from wing tip to root as he hit us amidship and passed under our plane. It was my understanding when talking to the crew several days later that our guns destroyed the FW-190. All four engines shut down and our intercom was silenced immediately. We were burning and two B-l 7s ahead of us were also on fire and went down. Paul then ordered me to bail out and after a short discussion I left the co-pilot seat, grabbed my chest chute, poked the top turret gunner, went under the flight deck, poked Hink (N) – he poked Willie (Englehart) (B), then they went out the front hatch and me after them. The top gunner went through the bomb bay to the radio room – stuck temporarily on the bomb bay “V” struts. This all happened in seconds and was done orderly and in a professional manner by all concerned. Our crew was a disciplined and well-trained crew, thanks to Paul. I attribute our successful bail-out to that training.” [emphasis added]

Navigator Hink‘s statement: “Worcester had been told by Hildreth to get us out of the nose. I turned and saw the whole left wing in flames. I pulled Englehart away from his gun and we all three jumped. Ream in the ball turret was first to see the fire and came out of the ball only to find the waist gunners were still firing. He started to climb back into the ball but was barely in when the others saw the fire and started leaving. Meanwhile Hildreth had kept the plane in a level attitude although it was losing altitude rapidly. I had pulled my rip cord fairly quickly and by the time I had made sure the parachute was open and holding me, I looked down to where about 500 feet below me I could see “008” was still keeping level, although the whole left wing was a bonfire. A few seconds later the plane went into a spin, broke up and exploded…. It may have been only a minute, but I don’t believe many could have held that plane level in the condition it was in that long so that everybody had a chance to get out…. If there had not been so many individual acts of heroism that day, I believe Hildreth would have received at least a D.F.C. [Distinguished Flying Cross]….I don’t believe many could have held that plane level in the condition it was in that long so everybody had a chance to get out.” [emphasis added]

In a 1981 letter after visiting with Paul and Annie, crew member Bob Ream wrote: “Paul, you said dedication and effort was the reason for the survival of our crew. Also a bit of Providence. I believe that. I mentioned how we in the after section of the plane worked together for the benefit of all. I did not mention at the same time that your attitude of always doing your best, and doing all you could do, was responsible for your being a good pilot and the reason for our survival. If you had not done your best as long as it was possible to do anything, four of us back there would not have made it out of the plane.”

Survived The “Final Jump” But Captured

To get a full sense of the events after Paul told the co-pilot to have the crew bail out of the plane, the following consolidated account is taken from several of Paul’s written statements. So these are his words, albeit rearranged, unless in block brackets:

“After a short time (but seemed an eternity), I saw that I would have to leave the ship. She had just started into a spin. I removed my equipment and crawled to the escape hatch and took that final jump. I opened my chute immediately and watched my ship start to spin then disintegrate. I was startled at the sky that was filled with pieces of ships and so many chutes, it was like a dreadful nightmare. I soon dropped into a wooded area where my chute caught on the branches of a tree and I was eased to the ground. I immediately discarded the equipment and went to look for Ream. We were soon together and prepared ourselves for what we had no idea!

After reaching the ground, I joined my ball turret gunner (S/Sgt. R. E. Ream). We walked from 11:40 July 18th until late into the morning then we took a nap under a grove of trees just outside a small village. At daylight on the morning of July 19th a man came up to us and directed us to the village. We decided that we would make a break at the first opportunity. We were right in front of the village at a small crossroad, a farmer was driving a herd of cattle along peacefully when all of a sudden, we broke it out through a field. All the German men and boys around gave chase and started shouting when Ream could run no more, they closed up on us and captured Ream. I broke away again and hid in a nearby hay field. I stayed in the haystack until the German civilians and soldiers looked everywhere for me. They finally gave up so I took a nap. I was awakened by the drone of our bombers coming overhead.

I was away for about 32 hours in which I was trying to get to Switzerland. I was picked up by civilians (at 17:00 that afternoon) and turned over to a civilian policeman in a small village south of Kempton, Germany. This civilian searched me and would not give me a receipt [for] confiscated personal belongings. I was relieved at the same time of the escape kit, which had been issued to me by my squadron. At this time there were no members of my crew or other American soldiers present.

A friend of mine [Lt. Timothy Gunn] was a pilot in a plane that was flying in a tight formation. The plane blew up, and the Germans made me search for the remains of the aircraft. I found the plane. My friend was still strapped in his seat. Crew members were taken from the rear section of the ship, which was intact. It looked as if the front section bIew up. I did pick up small pieces of bodies over about 2 acres of field and placed them in a wagon. That was the worst experience of the whole tour duty.

We were given a glass of beer and a slice of bread between the two of us [Hildreth and Ream] after finishing our work. We were then turned over to the German army and sent to Kimpton (by truck) to the Headquarters of the 91st Infantry Battalion. I saw my co-pilot, waist gunner & ball turret gunner there and we talked about all the other members of the crew. I was very glad that there were not injured seriously and all had left the ship OK.

At Kempton, Germany an English-speaking captain was in charge of us. I asked him for a receipt [of personal belongings taken] but instead he went to check, and on his return, he told me what was turned in by the civilians.

We were sent from there to Memmingen and turned over to the Luftwaffe on July 20th. I left there and was sent to Frankfurt and arrived July 22nd. [Dulag Luft, the Luftwaffe central interrogation camp, was at Oberursel, a suburb of Frankfurt.] Here I was thrown into solitary confinement until July 29th. I received two slices of bread twice a day and a small container of soup once a day. This was one of the worst times I have ever experienced.

I had no idea what to expect! On July 28th I asked to see an officer who I persuaded to let me have a bath and shave. The next day I was escorted to an interrogation officer and was drilled on all military matters pertaining to me. I gave name, rank & serial no. as ordered by our Army.

I left there with the remainder of my crew. H, I, R, W, K, B, W [Letters likely represent: Hink, Englehart, Ream, Worcester, Koller or Kettle, Bardon, Wylie] had gone on before to the permanent camp. B [Bardon?] was left behind at the hospital for medical treatment. We arrived at Wetzlar, a transient camp [near Frankfurt], where we were given a Red Cross kit containing tooth brush, powder and several necessary items of clothing. We arrived at our permanent camp Stalag Luft I at Barth Germany on August 1st .”

From the vantage point of the U.S. Army Air Force, its Missing Air Crew Report provides a real-time witness statement of the air battle and, then, after the war, statements from the crew. In its after-event report, the 483rd commanding officer called the air battle a “gallant chapter in the history of the 483rd….[and] established a fighting tradition which we must continue to uphold.” The German counterpart to these accounts is its Downed Allied Aircraft Report (with an English translation).

In sum, while the Hildreth crew members were all dispatched to POW camps, theirs was the only entire B-17 crew out of the 14 downed aircraft in the Memmingen Raid that survived after having their plane destroyed and parachuting into German territory. For the 483rd, the crews faced the enemy without fighter cover before the bomb run even began. Despite wearing silk tie maps, the officers were not able to escape once they reached the ground. The bravely of the crews to complete the mission despite so many B-17s shot down and men lost or captured is recognized as perhaps the 15th Air Force’s greatest air battle for which the 483rd was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation.

CRASH SITE OF ‘HILDRETH BOMBER’

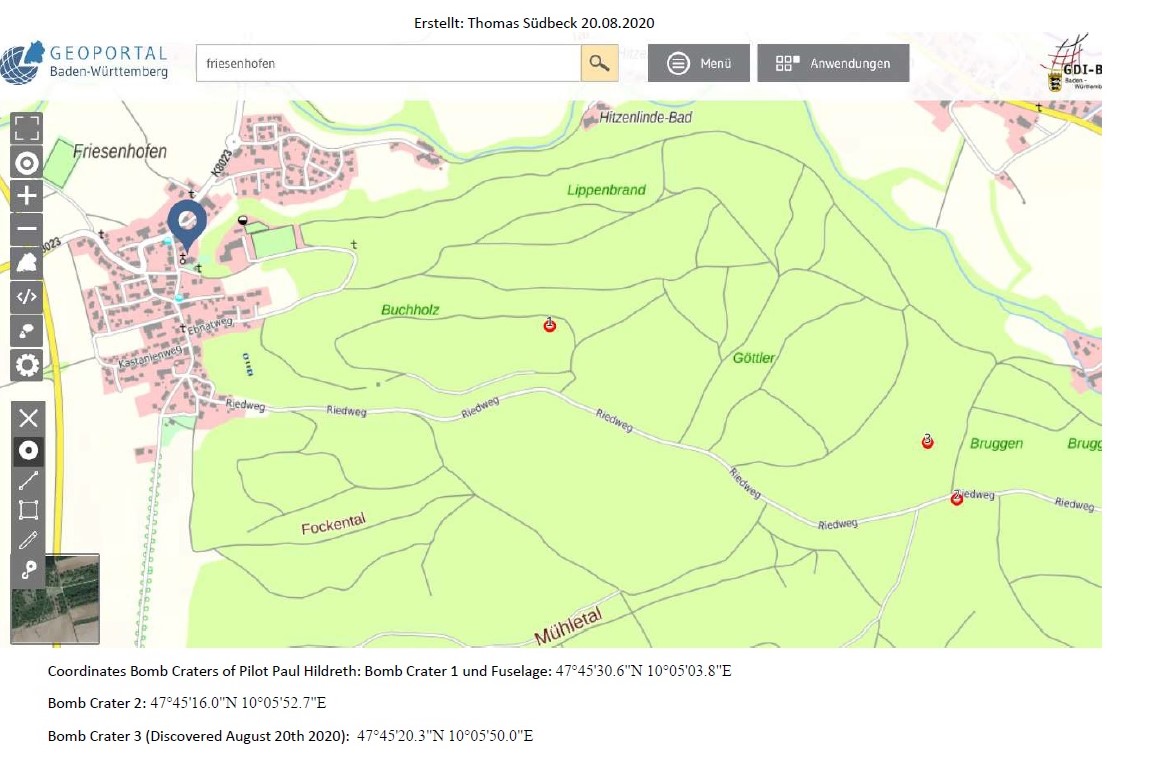

Not until 2018 was the crash sites of the destructed ‘Hildreth bomber’ found, and only then by the work of determined local civilian voluntary archivist Gerhard Schmaus along with earlier work by Ludwig Hauber and Thomas Sudbeck. They tracked down old accounts and located physical remnants to finalize the geolocations. Several of the locally identified sites of the debris field from ‘008 (as shown on the map below that was provided by Thomas Sudbeck) were further away from the other B-17 crash sites from that fateful day. Apparently, the crash of the ‘Hildreth bomber’ was the last to be found of the American B-17s shot down that day with pieces strewn across a wide area of Friesenhofen in Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany. In a generous gesture, several pieces of ‘008 were given to the Hildreth brothers.