Internment, Liberation and Repatriation

Paul Hildreth and his crew carried out a harrowing mission targeting the Memmingen airdrome which led to the crew’s capture as prisoners of war. Their story is one of courage, camaraderie, and ultimately, liberation.

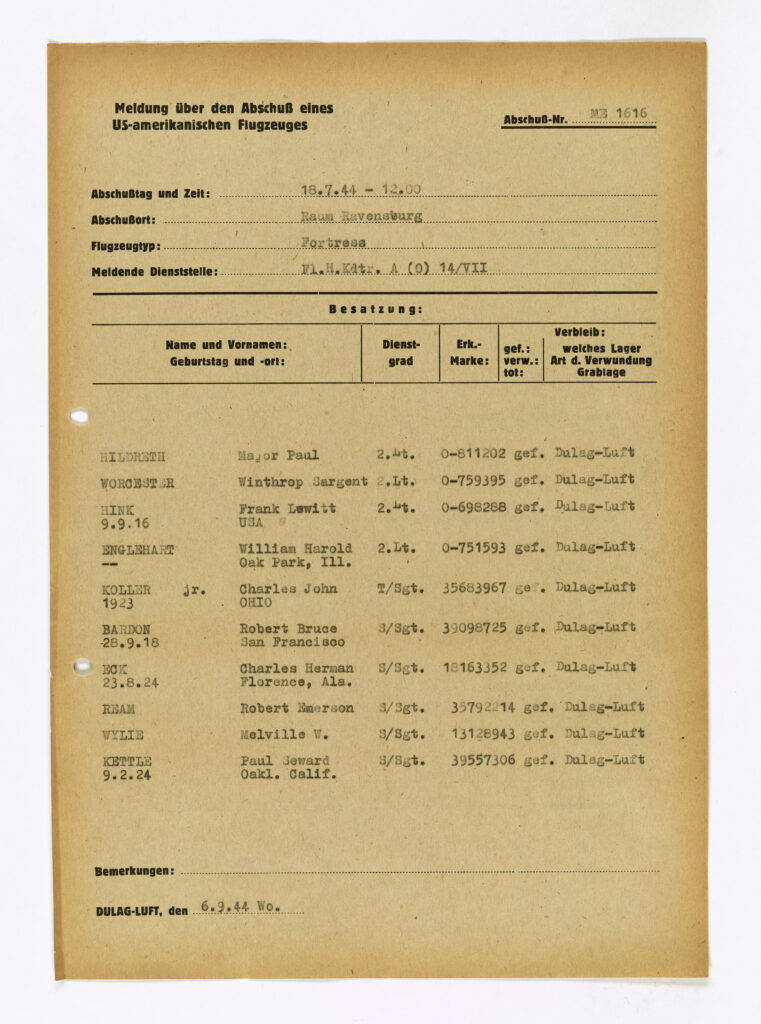

That fateful journey started on July 18, 1944 when Paul Hildreth and his crew had to parachute out of a burning aircraft. Their objective that day was to deliver a payload to a strategic location, but during the mission their aircraft was shot down. Paul Hildreth and his crew found themselves in enemy territory, captured and labeled as prisoners of war. He was interrogated near Frankfurt and then transported by train to the P.O.W. camp where he would spend the remainder of the war.

Internment

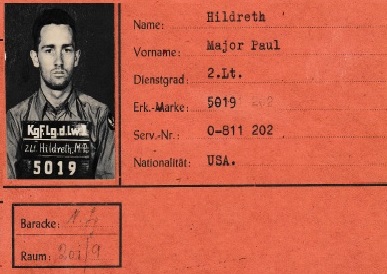

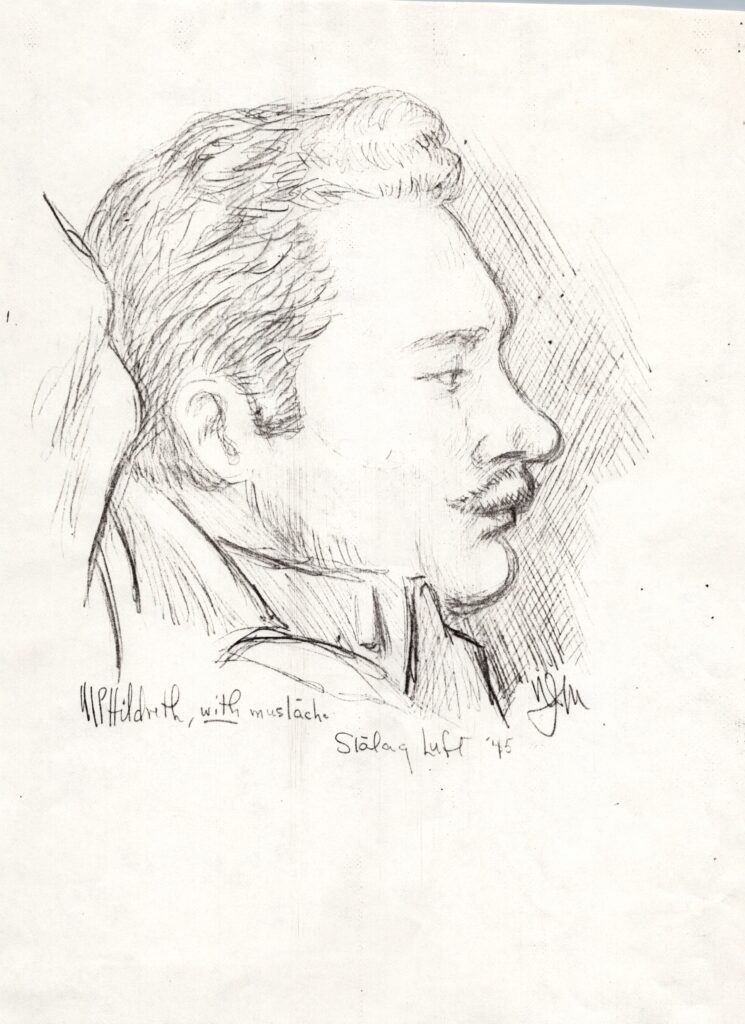

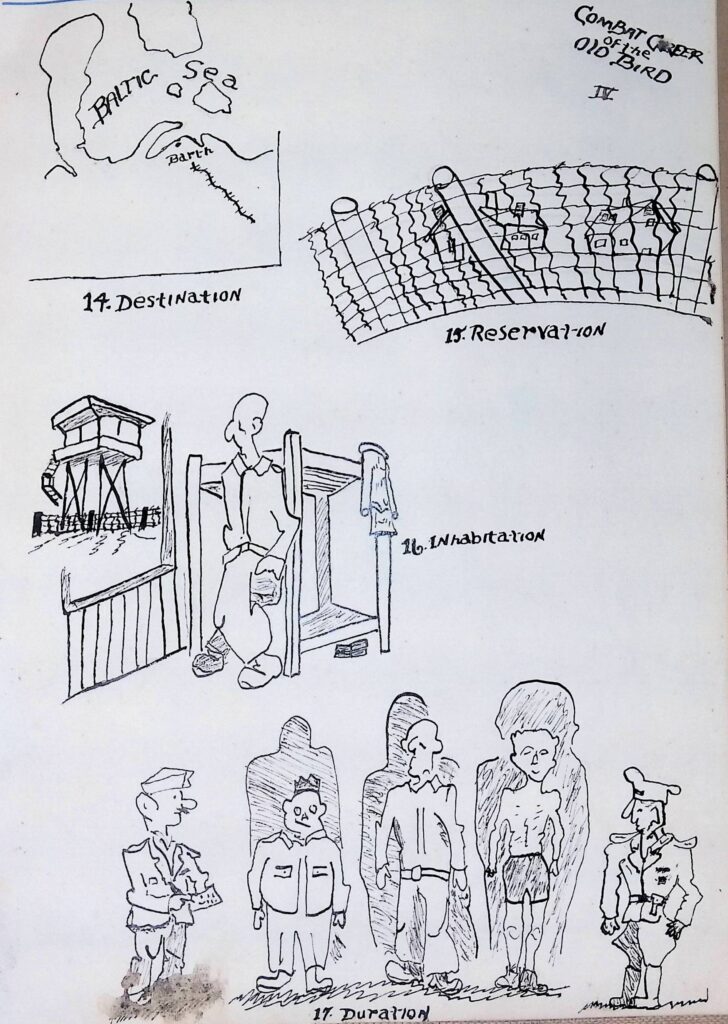

Paul Hildreth arrived at Stalag Luft I, or as he referred to it as ‘Barth on the Baltic,’ on August 1, 1944. Paul was P.O.W. No. 5019 (with the number starting ‘5’ signifying that he arrived after July) and housed in North Compound 2, Block 1, Room 9. At one point, there were 1,835 prisoners in that Compound, with each Block a separate building. Room 9 housed 20 men and was small (about 16 feet by 24 feet) with cardboard insulation for protection against the bitter cold environment. The men called the room ‘City Hall.’ American Army Air Force P.O.W.’s in the North Compound were organized as the USAAF Provisional Group V. The editor of the camp underground newspaper called Stalag Luft I “the house that flak built” because it housed the pilots, bombardiers and navigators downed less by bullets than by flak. The internees referred to themselves as ‘Kriegies’ which was short for the German word for war prisoner, Kriegsgefangener.

While interned at Barth, Paul and the other Kriegies were frequently startled by numerous rockets (later identified as testing of the V2) fired from the German testing center at Peenemunde, about 60 miles down the Baltic coast. Peenemunde was the technical site where the future of weapons of mass destruction were perfected by rocket engineer Wernher von Braun, who later developed U.S. ballistic missiles and space rockets. Peenemunde was a target of Allied bombing while Paul was interned at Barth.

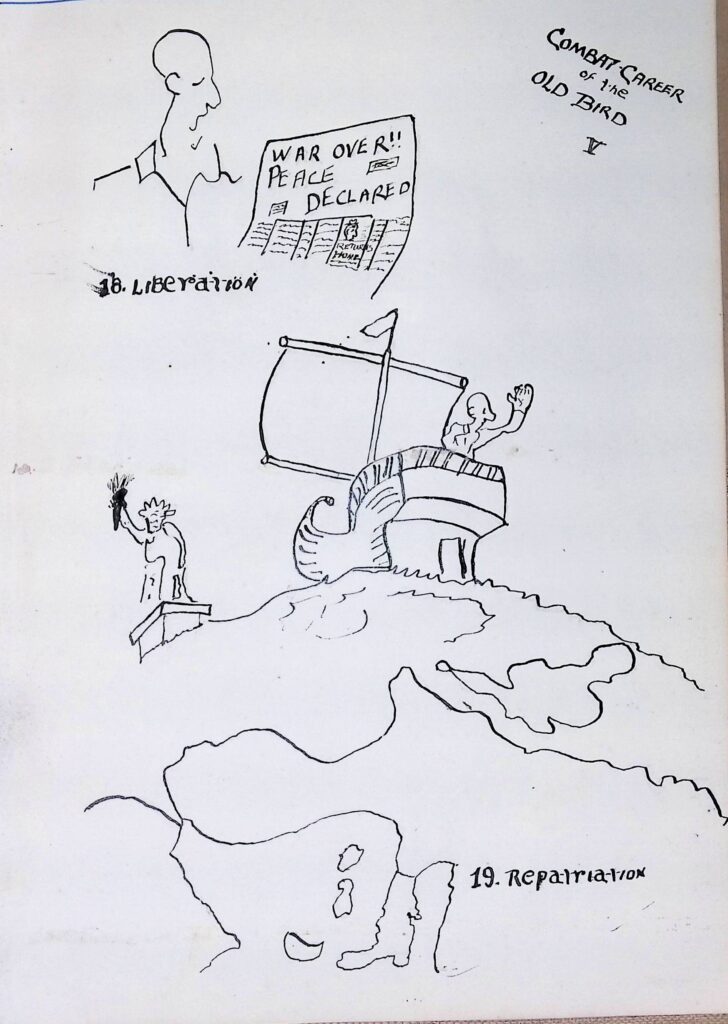

Paul’s American YMCA-provided ‘A Wartime Log‘ offers clues to his life as a Prisoner of War. It includes drawings, lists, poems (likely from others), and the names and home addresses of fellow Kriegies in his ‘City Hall’ room and of others in the camp from Alabama. There were drawing and sketching ‘classes’ taught by other P.O.W.s that Paul may have ‘attended’ to perfect the skills demonstrated by his drawings.

In another document, Paul wrote about life in the camp: “On our arrival to our permanent camp we were asked a number of questions by the German officers. We were then marched over to one of the old compounds to live until our compound was finished. I saw [Stanley] Perlman, one of our boys that went down earlier. Also, several fellows I knew in training. We live in tents that aren’t too uncomfortable now but we hope to move into barracks soon. We have nothing to do but eat and have roll call twice each day. Our greatest events are when the Air Force pass over our camp on their ways to the target.

We moved into barracks in the new compound on Sept. 12. Here we do our own cooking and etc. It would be fine if we had the food to cook, however at the present we get very little from the Germans but we get a box from the Red Cross consisting of Spam, Corned Beef, Salmon, dried milk, coffee, butter and candy. We all look forward to meal time. Times passes slowly here. No word from home as yet.

[Red Cross packages also included cheddar cheese that frequently showed mold spots. Paul later recounted that he would get the discarded ‘moldy’ cheese chunks from others knowing that he could salvage most of the cheese. It is unclear if he participated in the camp’s organized food exchange termed ‘Foodacco‘.]

Nov. 25 – a great day today. A letter from Annie and from mother and Dad. I am so glad to hear that they are all well and happy. We saved up our food for Thanksgiving however we had to limit ourselves a great deal since the amount of food we get from the Red Cross has to last us for two weeks.

Time slowly drags on here in camp and as time goes by things become more critical. The transportation facilities in Germany continues to grow worse. Our Red Cross food parcels arrive irregular and the suppression causes a great amount of worry as we often times wonder where our next food will come from. The Germans ___ allow us to make the most of the things we have. They continually lock us out of our barracks and search for anything that we may have made of food that we try to save for the lean days. Our lights and water problems continue to cause a great deal of grief. The Germans notified us that we would have no mail service in the future. The Kriegie Prayer is “Please, Dear God, let this war end so that this life of hell will cease.”

The food situation continues to become more critical. We received 2 ½ food parcels Red Cross per man since Christmas. The German ration is hardly enough to keep alive. We continue to be told that we will be evacuated if the Russians should make a drive in this direction. A number of camps have already been evacuated. Sgt. Ream has been sent to our camp but have seen none of the other members of our crew.

We had two of our men shot during an air raid alert. Lt. [Elroy F.] Wyman was killed. The other man is still living. We never know one day whether we will be alive tomorrow or not. We live in hopes.

March 27, 1945 was the greatest day of bright life. We received Red Cross parcels. I wonder what could have brought the sudden change in the Germans. I was beginning to get so weak from hunger that it would tire me to walk around the compound. I have never realized the necessity of food so much in all my life. We are the happiest group of men at the present time that I think is possible under the conditions that we are now living. We are having much warmer days now and we look back on the Black days of winter with horror. Seeing the sun alone seems to cheer everyone up immensely. We all feel that we can certainly live through the remainder of the now as we look back on the past. I have received one personal parcel. It was certainly a cherished item since at that time we had nothing but German rations to live on.

F.D.R. death – notified of same at 11:22, April 13.”

Paul developed a condition of Chronic Bronchitis while a P.O.W: “The first symptoms of bronchitis occurred in January 1945 following a long severe cold. I was of course undernourished.”

While Back at Home…

Annie and his parents constantly worried about Paul’s wellbeing. There was a realization that something was not right when they had not received a letter from him for some time. The formal notification of Paul’s missing in action [M.I.A.] status came from the Army’s Adjutant General on August 1 by telegram, followed by letters on August 4, September 9, and on September 16. Annie received a letter from his commanding officer Fred J. Ascani, dated August 15, 1944, acknowledging that Paul was M.I.A. and concluded with this statement: “Major is one of the best formation pilots I have ever seen.” However, by referring to Paul by his first name (Major) instead of ‘Paul’, it indicates that Ascani was not that close to all his pilots.

In responding to Paul’s parents’ anxious request for more information, the Adjutant General wrote on August 19 that although he recognized their desire for more information, Paul’s name had not shown up on any P.O.W. listing from the International Red Cross. Finally, on September 21, a ‘relay listener’ of the short wave P.O.W. Program broadcast from Berlin reported the following message with an address as Stalag Luft I, Germany: “Dear Annie: Am now a prisoner of war. Am safe and in the best of health. I was not wounded. This is my permanent address. Please do not worry, Darling. The whole crew is safe. Let Mother and Dad know and give them my love. I have your picture. I miss you and hope we are together soon. All my letters will go to you. Send books, cigarettes and candy. Let all the rest know and tell them to write. All my love to the dearest person I know. – Paul.” A few days later she received a telegram from the Army’s Provost Marshall General reporting the full radio intercept. On October 4, she received the official notification of Paul’s P.O.W. status from the Army’s Adjutant General. Paul later said that his time as a P.O.W. was worse for his wife, mother and father “because they didn’t know what was going on. I knew.”

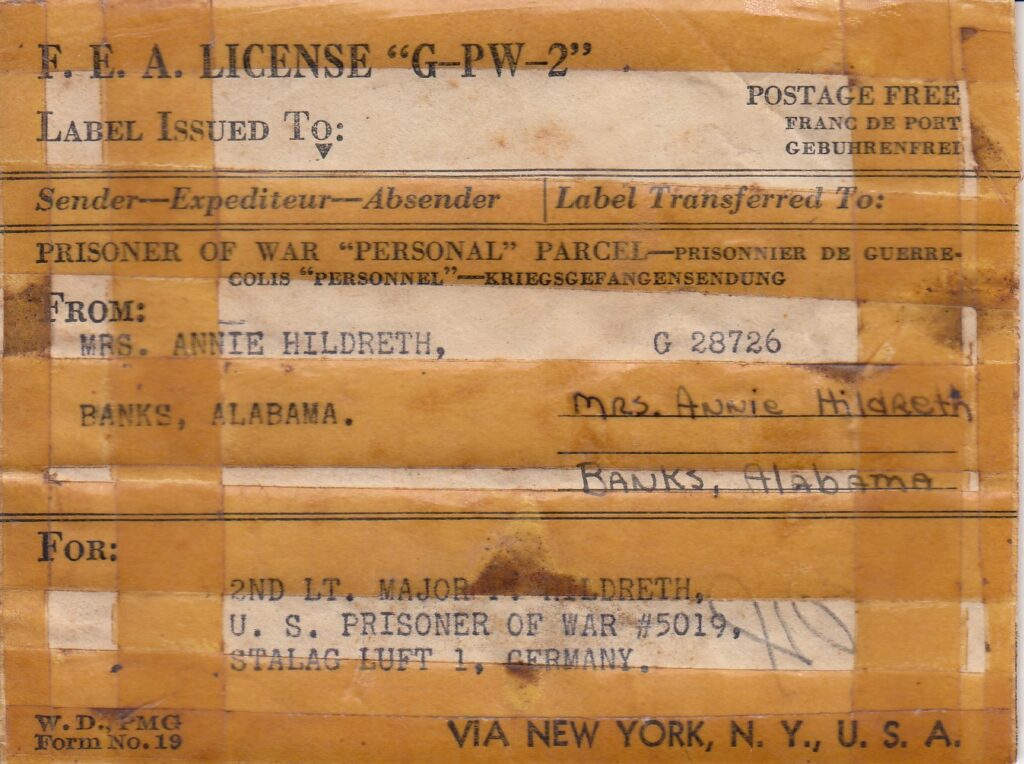

It was not until October 21 that the Army notified Annie which P.O.W. camp Paul was in, and his P.O.W. number, and gave her detailed instructions on the limitations of sending mail and packages to him. She ordered packages of supplies, such as fancy cigars, mailed to him. Sending mail was subject to censorship with at least one letter to Paul was rejected by the censors. Many letters from Annie and Paul’s parents did make it to him. In his Wartime Log, Paul noted that the first letters (dated September 27/28) from both Annie and his parents were received on November 25. In total, he received 35 letters from Annie and 13 letters from his parents. Mailing delays, from date mailed to received, ranged from a month to almost four months. In March, the Army sent Annie some of Paul’s personal effects that were from his Italy base. During Paul’s internment as a P.O.W., Annie devoted many hours to local Red Cross Activities and War Bond drives, and served as a substitute teacher of science in several local schools.

While M. Paul Hildreth was an American pilot in a German P.O.W. camp, his father-in-law, William Bartley Crawley, of Banks, Alabama (Pike County), was using German Prisoners of War from Camp Rucker, and the sub-camp in Troy, on the Crawley farm in Banks to harvest peanuts and cotton. The Troy camp was guarded by soldiers of Japanese ancestry from the Hawaiian Islands. Annie was known to be nice and friendly to the German P.O.W.s working on the family farm despite her husband being kept in a German P.O.W. camp, perhaps in the hope that Paul would be treated well, too. Her father was a leader of the group covered by the adjacent newspaper article wanting more German POWs for work on the local farms. This type of request persisted into 1945.

Liberation

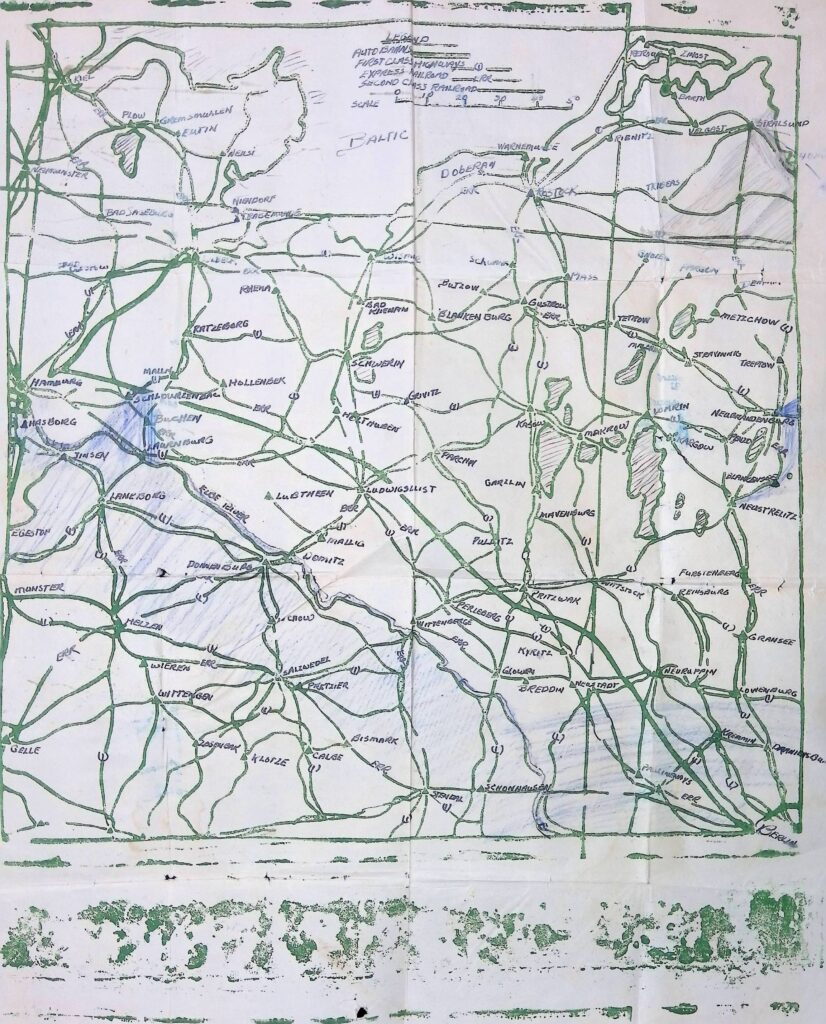

Captured military members enjoyed certain rights under the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Despite the difficult daily life of a P.O.W., the men looked forward to liberation. They tried to make life as pleasant as possible, with gatherings at Christmas and Karnival, for example. The Provisional Squad ‘I’ commander said Hildreth “volunteered for numerous details in an effort to benefit the squadron.” Once liberation seemed possible, they drew maps such as the mimeographed road map that he finished with town names, identifying Barth in the upper right and Berlin in the bottom right.

The German guards abandoned the facility ahead of the advance of the Russian Army. As Paul recounted: “At 10:18 PM, the first Russian Reconnaissance arrived at camp. On May 1, on our return from outside, we received news that Hitler had died, this news at 10:43.

[Crew co-pilot ‘Win’] Worcester was the first man in our compound to go over the fence. Our forces [Russians] took over at 02:00, May 1st. I was liberated by the Russian Army on May 1, 1945.”

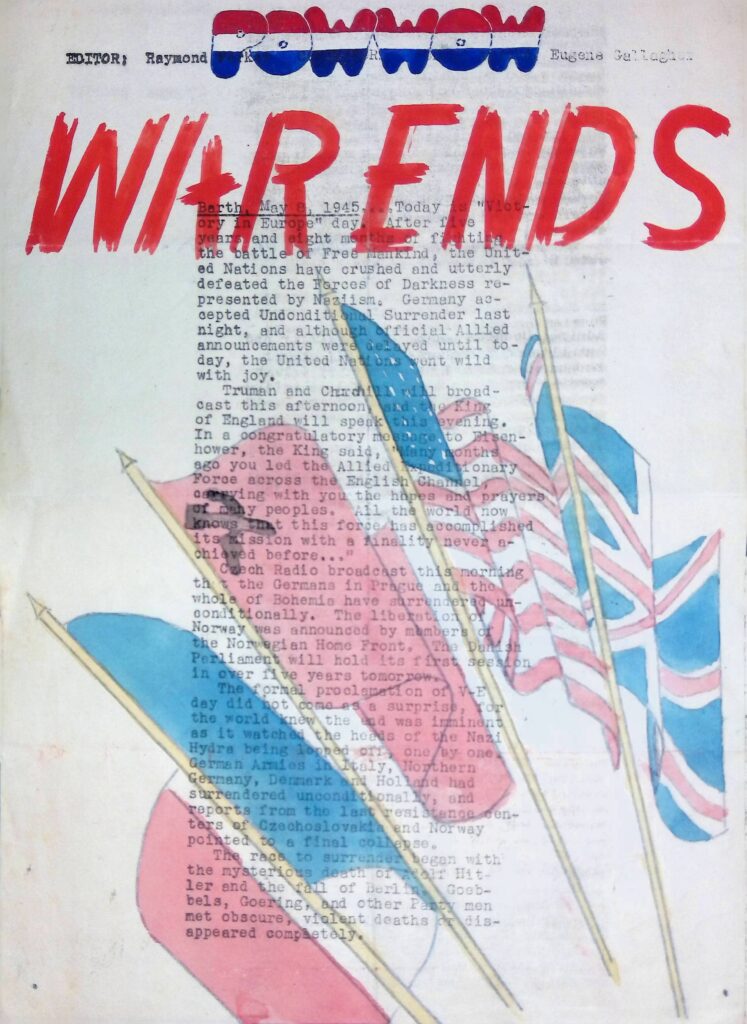

The end of the “barb bound community” was aptly captured in the “Russky Come!” headline of the P.O.W.-controlled Barth Hard Times two-page newspaper issued May 5, 1945. It provided details on the German plans to march the internees out of the camp ahead of the Russian advance but the senior Allied officers opposed those plans, with the German camp commander deciding that the German soldiers would abandon the camp, as they did overnight. The P.O.W.s had almost two weeks of freedom after the Germans fled, but the Allied camp commanders maintained a sense of military discipline to preserve order while awaiting transportation home. Although U.S. and British forces were only 75 miles away (in Schwerin), the Barth area was under Soviet control. Negotiation finally allowed 300 American B-17s to fly into the adjacent airfield and transport 30 men per plane to liberation. The airlift (see video) evacuation of 7,083 Americas and 1,415 British internees from Stalag Luft I began on May 12, 1945 and continued for two additional days, as recorded in several (additional) videos. This welcomed evacuation was termed ‘Operation Revival‘. (The Barth community later erected a plaque at the memorial park next to the site of Stalag Luft 1.)

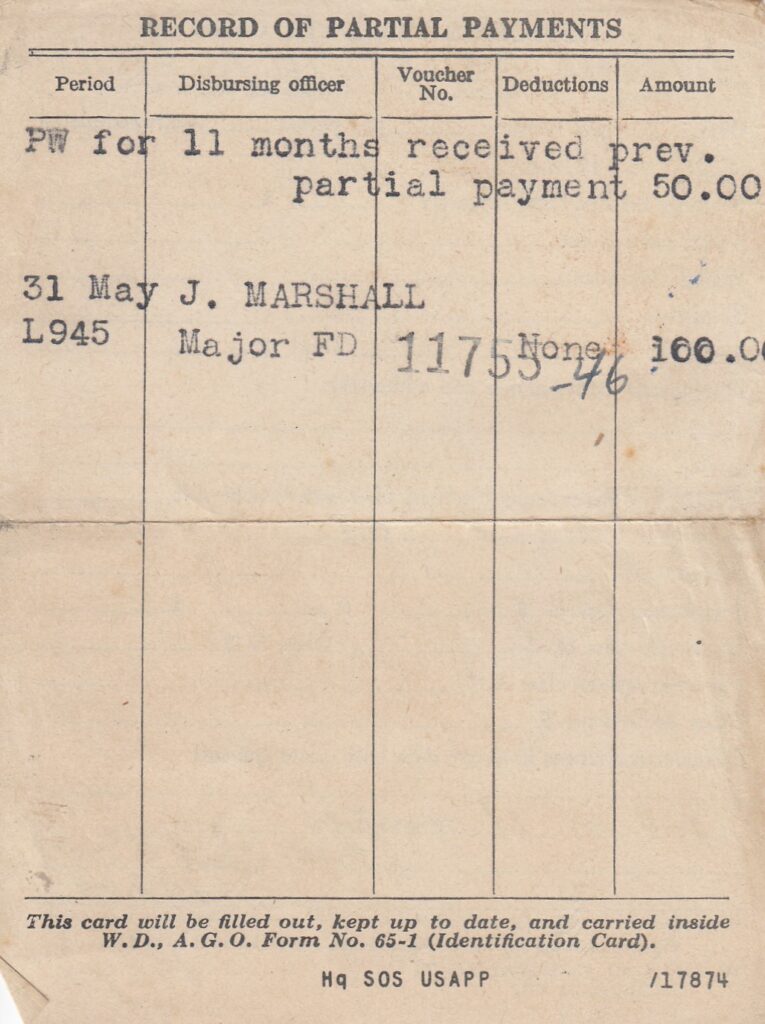

Upon liberation, Lt. Hildreth was first transferred to American military control at Camp Lucky Strike (RAMP Camp No. 1), a tent encampment, in Le Havre, France. The War Department sent Annie a telegram on May 25 that Paul was returned to military control as a released P.O.W.. While at Camp Lucky Strike, Paul received a ‘gratuitous issue of clothing‘ and was required to sign a certificate agreeing not to disclose ‘military information.’ On June 1, he was moved to England. While interned, Hildreth had received promotion to First Lieutenant (on August 7, 1944). With a little time to savor freedom first in Paris and then London, Paul enjoyed several local establishments, such as staying at the Jewel Club in London, visiting with a cousin, and purchasing perfume for his wife back home. Paul took advantage of his first name, Major, to secure extra leave and other informal benefits in the post-war excitement. His leave activities were possible once he received $150 for some of the time as a P.O.W.

Repatriation

On June 20, 1945, Major Paul Hildreth departed England as part of operation ‘Magic Carpet’ most likely aboard the USS General W.P. Richardson Navy troopship for his long-awaited return to the United States. The ship arrived at the Boston Port of Embarkation on June 27 and he was transferred that day to Camp Myles Standish in Taunton, Massachusetts. Given that he was currently unassigned, he was ordered to report to the Reception and Redistribution Station at Ft. McPherson in Atlanta, Georgia. First, he had to report to Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama for a physical on August 17 ahead of reporting to Gunter Field in Montgomery to fly again, this time in the AT-6D trainer, on August 23 and 28, for a total flying time of three hours. He was given leave on July 3 “for rehabilitation, recuperation and recovery” ahead of reporting to the Miami Separation Base. Back home in Brundidge, Paul was honored for his wartime service by driving the city fire truck in the V-J Day parade in August.

In reporting to the Miami Separation Base, the Army Air Force gave Paul hotel accommodations at the Whitman Hotel in Miami Beach, Florida starting September 2 for 28 days during September, with Annie permitted to join him for the first two weeks. At the beginning of the Miami stay, Paul was subject to the extensive physical examination for flying in which he was found qualified for oversees duty (although weeks before all former P.O.W.s were exempted from further service) and then at the end of the month he underwent another, albeit limited, physical examination. Paul and Annie enjoyed the beach hotel and visits to Martha Raye’s 5 O’Clock Club on Collins Avenue, but were scared during the 100 mile-per-hour winds and high waves caused by the hurricane on September 15. In Miami, Paul piloted a B-17G for a 5 hour local flight. He received his Congressionally authorized ‘Mustering Out’ payments of $300 spread out over three months as part of the separation day schedule. On September 29, Paul was given leave until he reverted to inactive service on November 30, 1945 and on that date formally separated from active service at the rank of First Lieutenant.

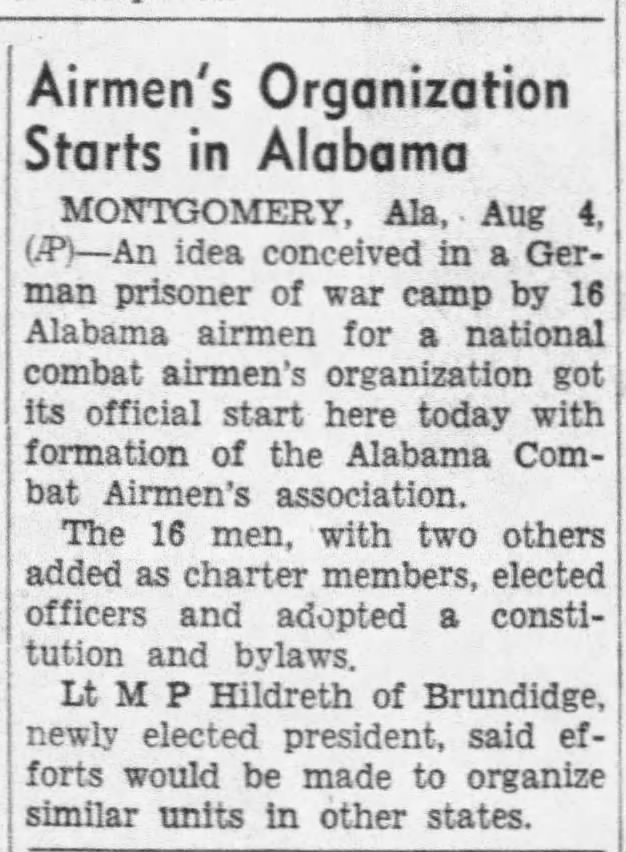

During his P.O.W. captivity, Paul conceived the need for a national combat airmen’s organization once they all got home. The concept was discussed among the Alabama airmen interned with Paul in Stalag Luft 1. That vision led to the incorporation of the Alabama Combat Airmen’s Association in 1945 with Paul as the elected President.

For his P.O.W. time (July 18, 1944 to May 1, 1945), the War Claims Commission awarded Paul Hildreth $288, amounting to $3.65 per day of internment.